Hi,

Titles, Purposive and Descriptive

I cannot get away with not offering a few thoughts on your substantive question about titles of artworks. I believe we have to draw a distinction between two senses of the term title as it is applied to an artwork: first, what I would call purposive title; that is, a title conferred by the maker or makers as an integral part of the artwork, and constitutive of it; and, second, what I would call descriptive title; that is, a convenient title by which an artwork without a purposive title might be known, conferred subsequent to the creation of the artwork by someone other than its maker or makers, in the absence of, or ignorance of, a purposive title. Confusion arises because a descriptive title can become an immaterial element of the artwork—being part of the sequence of adaptive uses to which that artwork is put—but it is not originally constitutive of it qua artwork.

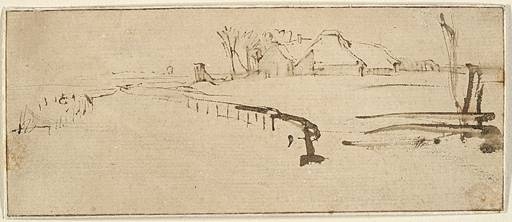

Insofar as philosophers have discussed titles, they have discussed purposive titles: notably Arthur Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1981), Chapter 1, and Jerrold Levinson, "Titles," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 44:1 (1985). Purposiveness and intention in respect of the artwork as originally constituted do not arise in the case of a descriptive title. (Of course, a descriptive title must be distinguished from a special class of purposive title: that applied by an artist to an already existing artifact or other object, or even immaterial concept, as an act of appropriative designation, such as Damien Hurst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, being a shark in a clear tank of formaldehyde.) Calling Harvard Art Museum 1932.368 (accession numbers are deliciously accurate and unambiguous, if random!) Winter Landscape is no different in this sense from calling it Blue Guitar; except insofar as we expect a descriptive title to be plausibly descriptively, and whereas the former is, the latter clearly is not. Yet even if we agreed to call 1932.368 Blue Guitar, this title would not be what Levinson terms in this context a plausible essential property of the artwork (for we are not dealing with the special case of appropriative designation). It would simply be misleading and wrong. Winter Landscape may be misleading and wrong, but was presumably conferred in good faith descriptively, just as Landscape with a Farmstead was subsequently to the same artwork. The drawing is depictively ambiguous. This in itself neither makes it nor disqualifies it from being good. It is demonstrably open to various first order interpretations. Is this a weakness? Not if one follows Rosand (which I do, though only so far) and acknowledges that a viewer’s interest in the drawing is not confined to its mimetic quality, but extends inter alia to other physically discernable factors (ductus, ink, paper). (I purposefully avoid inferred qualities that Rosand values—such as expression—about which I have reservations.)

Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch (1606 - 1669), Landscape with a Farmstead (“Winter Landscape”), c. 1648-1650, Brown ink, pale brown wash, and incidental marks in black chalk on cream antique laid paper, prepared with light rose-brown wash, 6.7 x 16 cm, Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Charles A. Loeser, 1932.368

In any event, I do not think any the less of the Landscape with a Farmstead (“Winter Landscape”) for its depictive ambiguity. Whether that ambiguity is itself purposive is the next question. Can we infer intention in this respect on Rembrandt’s behalf accurately? For now, I would reserve judgment, but this might be an issue to explore through close looking. (For, as philosophers know, Wimsatt and Beardsley did not make intention go away, any more than did Barthes & al.)

Ever,

Ivan