Imagination and Retrospection in 'the space of a door'

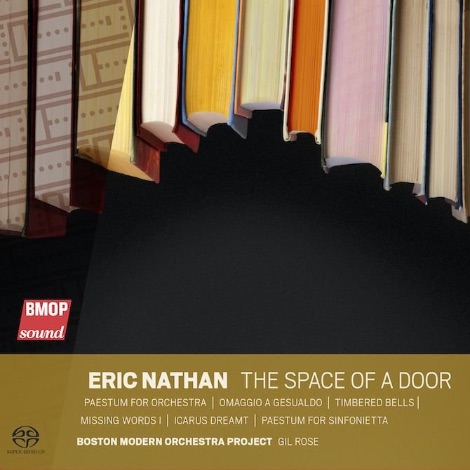

Album cover courtesy of BMOP/sound

These last few months have prompted some nostalgia in classical music. Audiences and musicians yearn to return to the concert hall; many orchestras have been streaming the Great Performances of yesteryear. And then there’s the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, which does not let a pandemic deter it from looking forward. In the space of a door, a superb disc released in May, the BMOP explores the music of Eric Nathan. Spanning works from his student days at Cornell to more recent activities (Nathan has taught at Brown since 2015), the album is a collection of luscious soundscapes that abound with imagination, spontaneity, and—in keeping with the prevailing mood—thoughtful retrospection.

the space of a door, the titular composition, was commissioned in 2016 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It begins like a Big Bang: nothing, and then all hell breaks loose all at once. The horns, entering with a minor third played in harmony, travel up another minor third and explode into a C major orchestral crash, setting off an extended frenzy of brass fragments, percussion blasts, and sustained high strings. Nathan writes that he intended this opening gesture to echo that of Brahms’s Symphony No. 2. The dual minor thirds are a clever homage, to be sure, but the symphonic parallel that keeps coming to my mind is the finale of Bruckner’s Eighth. What the two pieces share is a feeling of expansion and expansiveness, though they convey it in different ways. Whereas the Brucknerian machine drives unrelentingly onward with unstoppable force, ever-approaching the light at the end of a widening tunnel, the space of a door revels in the unexpected. The music seems surprised to find itself in the midst of so much happening, like someone who steps through a door and finds on the other side a brighter, loftier room than she had imagined.

Other delights include Missing Words I (2014), a set of miniatures based on entries from Ben Schott’s book of invented German words. “Herbstlaubtrittvergnügen” (“Autumn-Foliage-Strike-Fun”) features hilariously off-kilter horn glissandos, while “Fingerspitzentanz” (“Fingertips-Dance”) has the strings using their actual fingertips to play a sort of snap pizzicato. In Icarus Dreamt (2008), the twittering woodwinds and alternating moments of lushness, frantic energy, and anticipatory calm conjure for me the image of a forest teeming with life. It’s a nice, green place in which to imagine Icarus still soaring, having escaped his death over the bleak open sea. Paestum (2013), according to Nathan, was inspired by the ruins of the namesake city of Magna Graecia. The album is bookended by two versions of the piece, one for orchestra and one for sinfonietta. The former, to the credit of Gil Rose and the BMOP, creates a fuller, more sonorous tone while preserving a chamber-like clarity.

The piece that leaves the deepest impression is Omaggio a Gesualdo (2013). Scored for string orchestra, it pays tribute to the past without being too literal-minded. Not that there is anything archaic anyway about Carlo Gesualdo, whose complex chromatic harmonies and grisly personal life are both still shocking to hear today. Nathan takes the musical ideas of the madrigal “Ahi, disperata vita” (“Ah, desperate life”) and abstracts them to their limits. Gorgeous color shifts are punctuated by textural contrasts and the interplay of different voices, reflecting something of the egalitarianism of late Renaissance polyphony. The madrigal’s central motif, a descending four-note scale, transforms into little darting ornaments that flit about on the periphery, like a gloss in the margins of a manuscript. Finally, in a shimmering, solemn passage, the motif’s original form emerges, and the piece seems to finish on the familiar Phrygian half cadence which proclaims to the world, “I am old music.” Don’t be lulled by this momentary comfort. The music goes on, the dissonance creeps back in, and the real end of the piece is a reprisal of the funhouse version of Gesualdo’s motif in a soft smudgy murmur of strings—fading away almost as an afterthought, yet at the same time pointing emphatically, unmistakably forward.

Kevin Wang is a DJ for the Classical Music Department.